Even if you can’t read the characters, sometimes context clues will help you out

你会说中文吗 ?Nǐ huì shuō Zhōngwén ma? (Do you speak Chinese?)

As a native English speaker born and raised in the United States, I have to admit that I was never too fazed by foreign travelers speaking to me in English; I was always more interested in hearing their own languages.

So imagine my surprise when I traveled to China and found that simply the ability to say to say “你好 ni hao”—the standard, formal version of “hello” in Mandarin Chinese—was sometimes more than enough to dazzle Chinese locals.

My friend loves to tell the story of the time he used his two weeks’ worth of Chinese to tell a shopkeeper that he was “a student at Peking University”—I don’t know how to translate her excitement into words, but know that it was a full-body motion. Had I known beforehand that that was all it took to impress, maybe I would’ve studied less.

Just kidding. One of my main motivations for going to China, after all, was for the opportunity to learn Chinese in its native context.

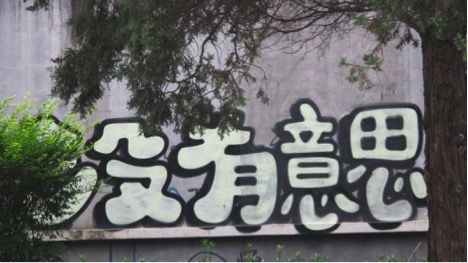

This graffiti in Beijing’s 798 Art District felt like it was made for novice Chinese learners.

Even though I went there straight after studying it for a year at college, I felt anxious about putting my language skills to the test. In hindsight, I can say that my concerns were simultaneously justified and excessive. Yes, it’s best to have some basic Chinese ability, but it might be more attainable than you think.

Overall, I would say that the average English proficiency level in China is fairly low (and therefore not something you should rely on). Of course, it depends on where you are and who you’re speaking with. When I visited Shanghai, for example, people typically spoke to me in English before I even got the chance to try my Chinese. In Beijing and Hangzhou, on the other hand, things went more smoothly when someone reasonably proficient in Chinese was around.

Regardless of where you end up, however, if you have any plans of getting out of the most tourist-y areas in China (and hopefully you do), trying to get a grasp on the language is good not only for your own benefit, but also as a way of reaching out and engaging with the host culture.

Learn the Basic Phrases Before You Go

Language partners (like mine on the far right) can be both great friends and resources.

The basic phrases that you need to survive in China are more or less the same you’d need anywhere:

- “Hello, my name is…”

- “I am [nationality].”

- “How much does this cost?”

- Please, thank you, excuse me, sorry

- Your occupation/reason for being in China

- Numbers 1-1000, useful for making purchases (and simple once you’ve memorized 1-10)

- The words for basic food items/characteristics, and how the written characters both look and sound (e.g., chicken, vegetable, rice, noodles, spicy/hot, sweet, “I don’t eat meat,” etc.)

- If worse comes to worst: “Sorry, my Chinese isn’t very good. Do you speak English?”

The above phrases were enough to get me through almost all my everyday interactions. (The exception would be riding in a taxi, which can require a bit more finesse; if you’re not confident in your skills, I’d recommend either bringing someone who is and/or writing your destination down.)

There are certain nuances you’ll want to learn—such as the art of bargaining—but those mostly come with real life experience.

A Little Bit of Effort in Speaking the Language Goes a Long Way

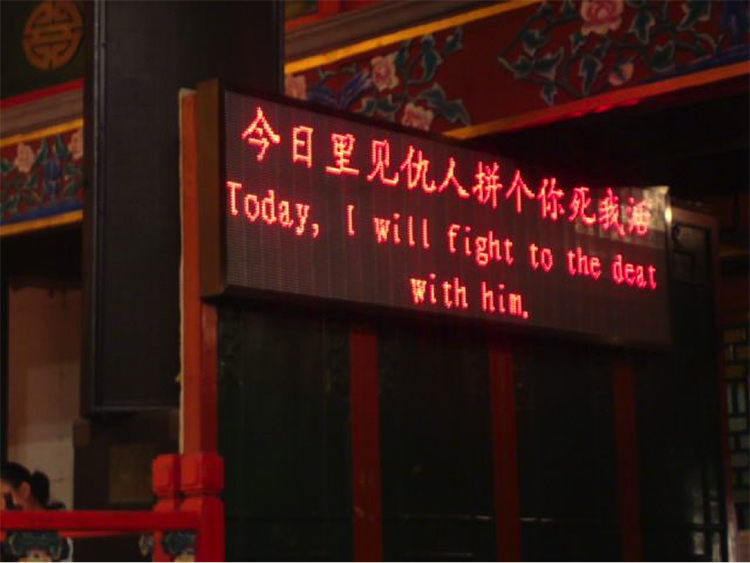

Certain vocabulary words probably won’t show up in your average textbook, in which case English translations are much appreciated (like at this Peking opera performance).

However, more important than any specific vocabulary word is the fact that, in my experience, people in China will typically appreciate any honest attempt to speak their language. In fact, they’re often even flattered by your apparent interest in their culture (you came all this way, after all). So people are generally pretty forgiving if you pronounce things incorrectly, or if your tones are a little off.

In fact, one of my biggest regrets is that I took way too many excuses to not have to struggle to speak Chinese myself, such as the fact that I was with friends with better Chinese than me, or that whoever I was speaking to seemed to speak enough English for me not to bother. Sure, I guess it did make life easier and saved me from any feared embarrassment, but in the end all I really did was miss out on a lot of great opportunities to improve myself.

Truly attempting to learn another language is one of the best avenues out there for receiving a more authentic experience and expanding your perspective. If you take anything from all that I’ve written here, I hope that it’s the motivation to try at least a little every day.