I was staring blankly at the empty notebook pages I was to fill up with notes in a language I did not understand, when suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a dark shadow move towards me. ¨This is what the end feels like,¨ I thought. I had left home barely two weeks ago, and I was already kicking myself for thinking this was a good idea.

The shadow moved closer. ¨I am not an adventurer. I am a sixteen year old girl who let her ego send her part-way across the world for ten months.¨ The shadow stood before me, and before I could decipher what was going on, the notebook in my hand transformed into a college rejection letter. ¨How am I supposed to pass my classes if I can’t even speak the language they are taught in?¨

My mind was reeling over all negative possibilities; being kicked out by my program for having bad grades, needing to retake my junior year of high school, slaughtering my GPA and being turned down by colleges. The shadow churned these thoughts around and around in my head.

The Many Disguises of Culture Shock

This culprit goes by the name of Culture Shock. Its mastery of disguise puts even the invisible cloak from Harry Potter to shame. It appears in its many forms, including stress surrounding school, cultural assumptions or generalizations, trouble focusing, and homesickness, and attacks when least expected. There are many temporary remedies to dull its effect, but the only forces that can truly defeat it are time and courage.

The idea of going through Culture Shock is often rejected by many people, especially in the first few days of extended travel. Prior to your departure from home, you conjure this image of yourself leaving your comfort zone to see the world, and in the first few days this is usually what it feels like. Everything is new and exciting, and curiosity has become your new best friend.

When asked about Culture Shock, you brush it off as something other people experience or a side effect that will come later, and this is usually because your are in its first phase: ‘The Honeymoon.’ You are in love with your new home, and adventure is everything you had anticipated it to be. You have built this skyscraper of expectations, and all that is currently around you matches it perfectly.

Then, as time progresses, this tower begins to falter. The skyscraper gets shorter and the shadow gets larger, until all that is left is crumbling plaster and a nagging shadow that has replaced what once was curiosity. This is the gateway to the ‘What am I doing here?’ phase.

At around this time, Culture Shock whips out persuasion, one of its most hostile skills. It convinces its victim that it will never leave, and that whatever they came to gain or achieve is not worth the effort. It also enjoys leaving reminders throughout your daily life. That dog that is usually sleeping on the corner, that was once so cute, now brings to mind the cat you have at home. It does not matter if you were actually fond of the cat in the first place; Culture Shock just likes to make is apparent that the cat is missing from your current life. The flowers outside the window now remind you of your garden in your home country, and that makes you recall playing with your siblings in the yard, which reminds you of how much you miss your family. Culture Shock makes it difficult to see things as they are – flowers as flowers and dogs as dogs, not as broken pieces of a shattered life you will never return to.

This is when you must face the challenge of not turning away. If you turn away, Culture Shock has succeeded in defeating your will to achieve your goal, whatever that may be.

Stay Strong Through the Shadows

Having the courage to not run will allow time to work its magic. This is crucial, as time is the only thing that will bring you to the ‘Where’s the party at?’ phase. At this point, you begin to feel more at home in your host country. Language barriers have typically been lessened (if they existed in the beginning), and you are starting to develop a familiar schedule. You are likely adapted to life with your host family, and thoughts of missing home occur less often or it has become easier to manage those thoughts. Studies at Columbia University find that majority of students hit this phase around 3-4 months, but that, since everyone and their experiences abroad are different, it is hard to identify a consistent time.

As I am just now entering my second month abroad, I am still sorting through the remains of a demolished skyscraper, trying to find curiosity hiding among the ruins. I accept that all I can do is wait, and that eventually, my state of mind will be altered because that is what happens with time. Notice how every stage of Culture Shock is a ‘phase.’ It is not a permanent reality, but a string of moments that will pass quicker than you expect them to. As long as you have the courage to wait, you can find hope in the fact that you, and everything that drove you to leave your home country, will overcome Culture Shock. Shadows can be intimidating, but they cannot hurt you.

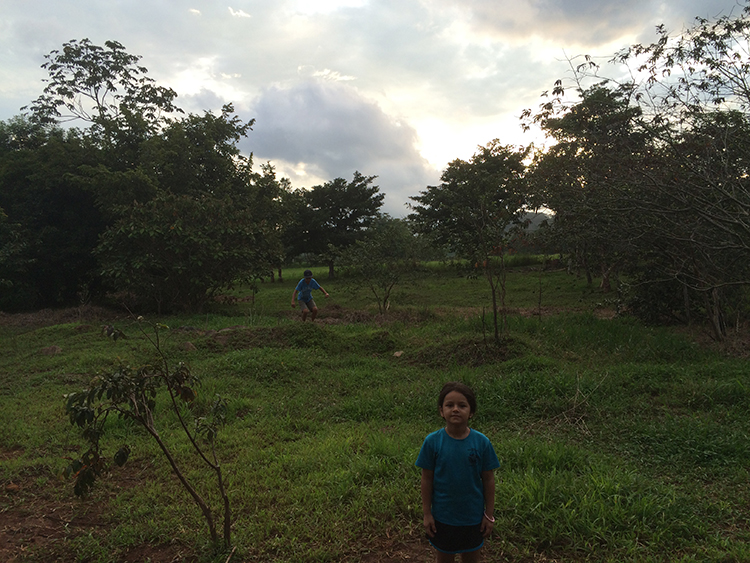

Here are a few photographs of the small things, and moments that make me smile:

About the Author:

My name is Rachael Maloney, and I am a curious venturer fueled by good books and foreign food. I am currently spending my junior year of high school in Costa Rica, doing my best to absorb everything my 10 months abroad have to teach. I look forward to carrying these lessons with me for many years to come, and, in the meantime, sharing them in online articles for those who are interested. Follow Rachael on her adventure and read her stories here.